Japanese Cinema: an Early Look

Japan has one of the oldest (starting in 1897), largest film industries in the world. Perhaps the Japanese took to cinema because of traditional frameworks such as the magic lantern (gentō) which works something like the old slide carousels. Gentō are so old that they were first lit by candles or oil lamps.

A hefty suspension of disbelief occurs in most cinema, coupled with strong moral and philosophical messages. Each film may also create its own visual “rules,” and all of this seems compatible with the stylized storyforms ranging from kabuki and noh/kyōgen plays to animé and manga. In my mind, cinema is the dominant form of storytelling today. The Japanese, with their deep grounding in Zen Buddhist, Shinto, and minimalist philosophies, seem to have a unique affinity for the medium of cinema.

This is a huge topic, and one I’ve been wanting to explore for some time. So I’ll do it in pieces, using both Wikipedia’s help and my own conjecture. First: some early background, with lots of ideas for films to see. I was able to find (and put a hold on) many of these films in my public library online; your nearby college library may also have some, with a mandate to serve the public as well. So this can be a recession-friendly exploration project, if you’re so inclined.

This is a huge topic, and one I’ve been wanting to explore for some time. So I’ll do it in pieces, using both Wikipedia’s help and my own conjecture. First: some early background, with lots of ideas for films to see. I was able to find (and put a hold on) many of these films in my public library online; your nearby college library may also have some, with a mandate to serve the public as well. So this can be a recession-friendly exploration project, if you’re so inclined.

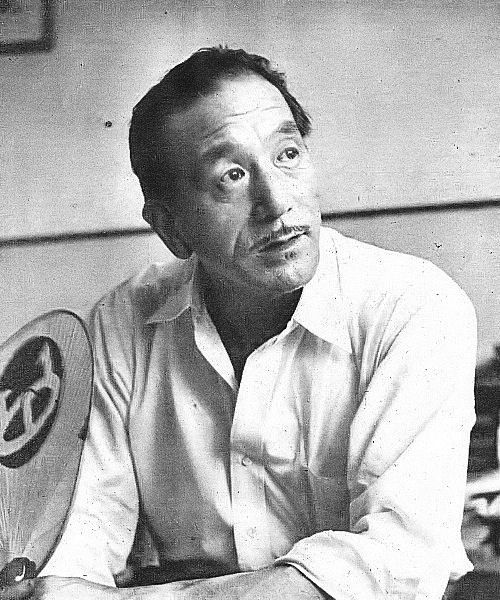

Movie poster for 1937 Japanese movie Sadao Yamanaka’s Humanity and Paper Balloons.

Early Japanese films (I’m talking before 1900) included horror/ghost films like Bake Jizo (Jizxo the Ghost), Shinin no sousei (Resurrection of a Corpse), documentaries like Geisha No Todori (Geisha Dance), and Momijigari (two actors performing a scene from the kabuki play of the same name).

Shōzō Makino, the pioneering director of Japanese film, was a creator (with Matsunosuke Onoe, his favorite actor who became Japan’s first film star) of Jidaigeki (時代劇?, period drama). Masao Inoue is widely believed to be the first director to use techniques new to silent film like the closeup and the cutback.

In the 1920s, directors such as such as Hiroshi Inagaki, Mansaku Itami and Sadao Yamanaka refined their visions at independent studios in Japan formed by Japanese movie stars. The proletarian arts movement of this time spawned the Proletarian Film League of Japan (Prokino for short), whose films documented demonstrations and workers’ lives and other tendency films, with left-wing and socially-conscious tendencies. The government arrested Prokino members and effectively crushed the movement, making political dissent dangerous and, perhaps, more alluring to filmmakers.

Unlike in the U.S., silent films endured well into the 1930s. Once talkies hit, some notable films from this time include Tsuma Yo Bara No Yoni (Wife, Be Like a Rose!, 1935); Yasujiro Ozu’s An Inn in Tokyo, a precursor to film neorealism; Kenji Mizoguchi’s Sisters of the Gion (Gion no shimai, 1936); Osaka Elegy, 1936; and The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums, 1939.

The government also began to be more involved, encouraging propaganda (like Sadao Yamanaka’s Humanity and Paper Balloons, 1937) and documentaries.

World War II was rough on Japan and national cinema suffered. The decade did debut the great director Akira Kurosawa, with Sugata Sanshiro, followed up by his Drunken Angel (酔いどれ天使, Yoidore tenshi) and Stray Dog (Nura Inu, 野良犬). Kurosawa was one of the most influential directors in the world. Yasujiro Ozu directed Late Spring (Banshun, 晩春) in the 1940s as well. After the war’s end, the floodgates of American animated films, previously banned by the government, showered the Japanese people. Could this, combined with the stylistic sophistication of Japanese theatre and film, have been a seed for animé?

Next up: a look at five Japanese films that are ranked among the best films ever produced.

[source: Wikipedia]